The Royale is loosely based on the life of Jack Johnson, the first black world heavyweight champion. In the play, his name is slightly changed to Jay Jackson.

John Arthur “Jack” Johnson began his professional boxing career in 1897. He made good money from his fights and quickly gained notoriety as a boxer. In 1903, he won the “Colored Heavyweight Championship of the World” but many white boxers still held the “color line” and refused to fight black boxers, especially for title fights. Johnson pursued a title fight with the current heavyweight champion, James J. Jeffries, but Jeffries refused. He retired undefeated in 1904.

Johnson then began to seek a fight with Tommy Burns, who succeeded Jeffries as champion. Johnson followed Burns all over the world for two years, trying to taunt him into a fight. Burns refused to fight Johnson for less than $30,000, which was nearly double what any champion fighter had won in a single fight. As a result, he believed he was reasonably safe from facing Johnson in the ring. However, in 1908, an Australian entrepreneur named Hugh McIntosh put up the money for the fight.

In Sydney, Australia, to a crowd of 20,000, Johnson toyed with the outmatched Burns. Johnson wanted the fight to go as long as it could, so he smiled and joked in the ring, fighting casually until the later rounds when he clearly dominated Burns. In the fourteenth round, the cameras stopped recording and police ended the fight before Johnson could knock Burns out. Johnson was declared the first black heavyweight champion of the world.

The next day, The Sydney Morning Herald wrote that Johnson’s victory was “received with marked disappointment by the 20,000 people present.” White journalists and writers were heavily biased against Johnson and white supremacist opinions characterized the coverage of the fight. The Chicago Daily Tribune’s editorial wrote: “The victory of Jack Johnson over Tommy Burns in Australia yesterday dethroned the white man from the place he appeared destined to hold as long as the game of fisticuffs held its existence. [T]he fact that the black defeated a white man points out only too plainly the lack of class in the present day crop of heavyweights." The new champion did not return to the U.S. in celebration. Although Johnson won the heavyweight championship in the same way as every other fighter, Johnson continued to face doubts about his legitimacy as a boxer.

The Fight of the Century

In response to Johnson’s victory over Burns, the media began to call for the undefeated Jeffries to come out of retirement and fight Johnson. Many people viewed him as the true champion and believed he was the only white boxer capable of defeating Johnson. Novelist Jack London wrote in his report of the fight for The San Francisco Call, “One thing remains. Jeffries must emerge from his alfalfa farm and remove that smile from Johnson’s face. Jeff, it’s up to you.” Jeffries became known as the “Great White Hope.” He had been retired for six years and was out of shape living on his alfalfa farm. He was not eager to come of retirement to fight Johnson, but he was besieged by the media and fight promoters to take up the challenge and reclaim the heavyweight title.

Jeffries was finally persuaded by both the social pressure and the fight promoter Tex Richard who guaranteed the winner two-thirds of the astronomical $101,000 purse. After agreeing to the fight, Jeffries said, “That portion of the white race that has been looking at me to defend its athletic supremacy may feel assured that I am fit to do my very best.”

The fight took place in Reno, Nevada on the Fourth of July, 1910. Leading up to the bout, the press extensively covered the training routines and lives of both fighters. There were nearly 22,000 boxing fans in attendance. Afraid of violence breaking out in the crowd, the promoters banned alcohol and checked audience members for firearms.

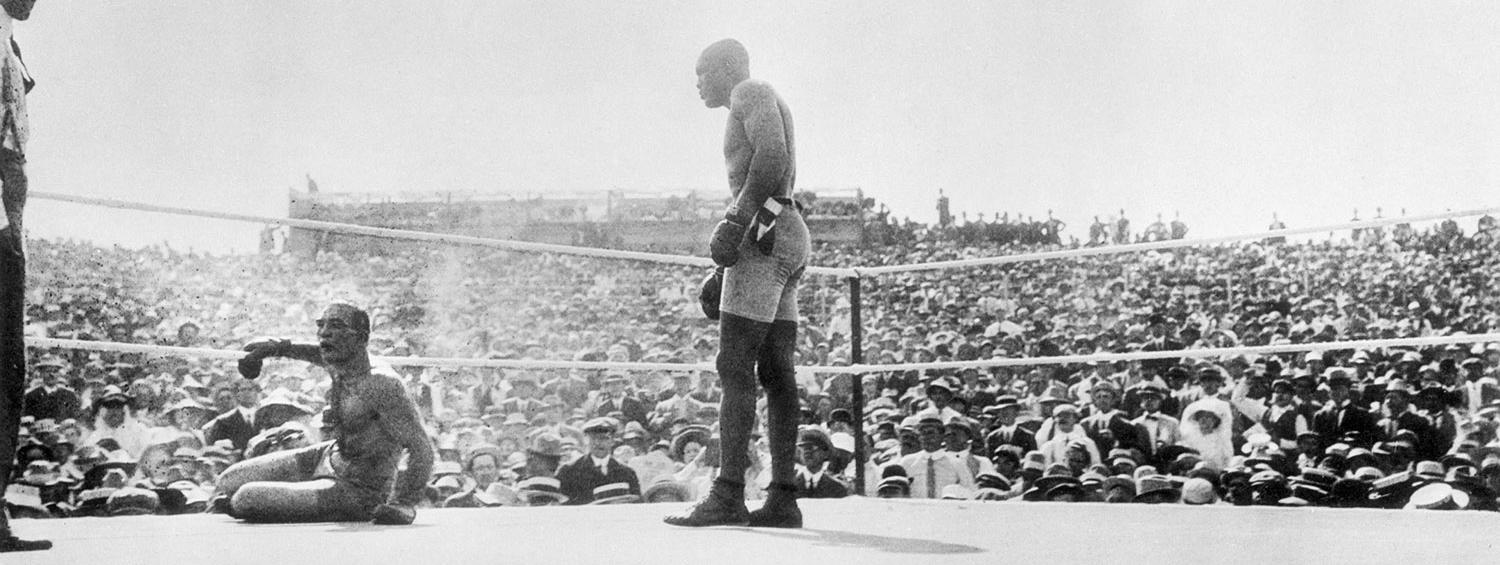

At the beginning of the fight, Jeffries refused to shake Johnson’s hand. Johnson came into the ring initially cautious, but after the sixth round, it was clear that Jeffries was no match for him. In his entire career, Jeffries had never once been knocked to the ground. In the 15th round, Johnson knocked Jeffries to the ground three times and Jeffries’ corner stopped the fight to prevent a knockout. After the fight, Jeffries admitted, “I could never have whipped Johnson at my best. I couldn’t have hit him. No, I couldn’t have reached him in 1,000 years.” Johnson had become the undisputed world heavyweight champion.

Personal Life

Jack Johnson began his boxing career in 1897, just a year after the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling which cemented the "separate but equal" doctrine during the Jim Crow Era. Part of what made Johnson such a controversial figure was his disregard for Jim Crow Laws. Defending the segregationist reality, Booker T. Washington said in an 1895 speech to the Atlanta Cotton States and International Exposition, “In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.” Johnson held a different view. In his autobiography, Johnson wrote, “I have found no better way of avoiding racial prejudice than to act in my relations with people of other races as if prejudice did not exist.”

In some ways Johnson angered white supremacists simply by dominating the news cycle and becoming one of the first African-American pop culture icons. Johnson rose to an elevated status that white people did not believe he should hold. He was the most photographed black man of his day and frequently made the front page of white newspapers. His personal life was publicized and scandalized; he was criticized for the cars he drove, the clothes he wore, and the hotels he stayed in. For the press, the most scandalous part of Johnson's life were the white women he slept with, dated, and married.

No other boxer would hold the championship for over two decades, and Johnson made an indelible mark on the sport of boxing. In the Ken Burns documentary Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson, Burns states, “Johnson in many ways is an embodiment of the African-American struggle to be truly free in this country – economically, socially and politically. He absolutely refused to play by the rules set by the white establishment, or even those of the black community. In that sense, he fought for freedom not just as a black man, but as an individual.”

The Mann Act

In 1912, Johnson was arrested for violating the Mann Act—a law that made it illegal to transport a woman across state lines for “the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose"—while traveling with his white girlfriend, Lucille Cameron. Cameron's mother called the police and accused Johnson of kidnapping. In 1913, an all-white jury agreed and convicted Johnson.

Johnson fled the country and lived abroad as a fugitive for seven years before returning and surrendering to a U.S. Marshall in 1920. Some speculate that Johnson intentionally lost his title to Jess Willard in 1915 because he believed the charges against him were retaliation for his victories and might be dropped if he lost the title. Whether true or not, Johnson served his year-long sentence in Leavenworth, Kansas after returning to the states.

After his release, Johnson continued to box, but with less commercial success. He officially retired in 1945. In 1946, while driving angrily home from a restaurant that refused to serve him, Johnson died in an automobile accident. In 2018, Johnson received a posthumous presidential pardon.

Box Office: 301.924.3400

Open Wednesday - Sunday: 12:00 PM - 6:00 PM