Miss You Like Hell is the story of a mother-daughter, cross-country road trip. Even before the invention of the car, the road trip story was a long held American tradition. Below is the history of the American road trip and cultural history of the road trip narrative.

History of the Road Trip

The American road trip tradition began as early as the 1900s. At the time, cars were not really constructed for long-distance travel, but a resourceful, wealthy, and knowledgeable driver could pull off a cross-country road trip. The first attempt to take a road trip across America began on a bet. In 1903, Horatio Jackson argued that automobiles were the future of transportation and decided to prove it by driving from San Francisco to his home in Vermont. Jackson didn’t own and had barely even driven a car. He hired a mechanic, Sewall Crocker, to serve as his back up driver, bought a car, planned a route, gathered gear, and started by heading north before proceeding east along the Oregon Trail. Richard Ratay described some of the trials they experienced along the way:

“Only 15 miles into their journey, the car blew a tire. On the second night, the men realized the Winton’s side lanterns weren’t nearly bright enough to light their way after dark, so they purchased a large spotlight to mount on the hood. Near Sacramento, they were given bad directions--on purpose--by a woman because she wanted her family to get their first look at an automobile. The detour added 108 miles to their route. In Oregon, the pair suffered two more flats. Lacking spares, they wound thick rope around the wheels as a makeshift substitute until they could find new tires. Not long afterward, they ran out of fuel. Jackson rented a bicycle and pedaled 25 miles to purchase gas, then rode back with four heavy cans strapped to his back. Along the way, the bicycle blew a tire. And all this was before the twosome had even departed the West Coast.”

The many obstacles to routine car road trips included the cost of autos, the lack of safe roads, and the limited resources along the way. In its early years, the automobile was inaccessible to most Americans. The average annual salary was $500 and automobiles cost between $650 and $1,300. Even if you could get a car, poorly-constructed roads, few garages, filling stations, and dealerships existed outside of city limits, which meant driving very far required a large amount of self-reliance.

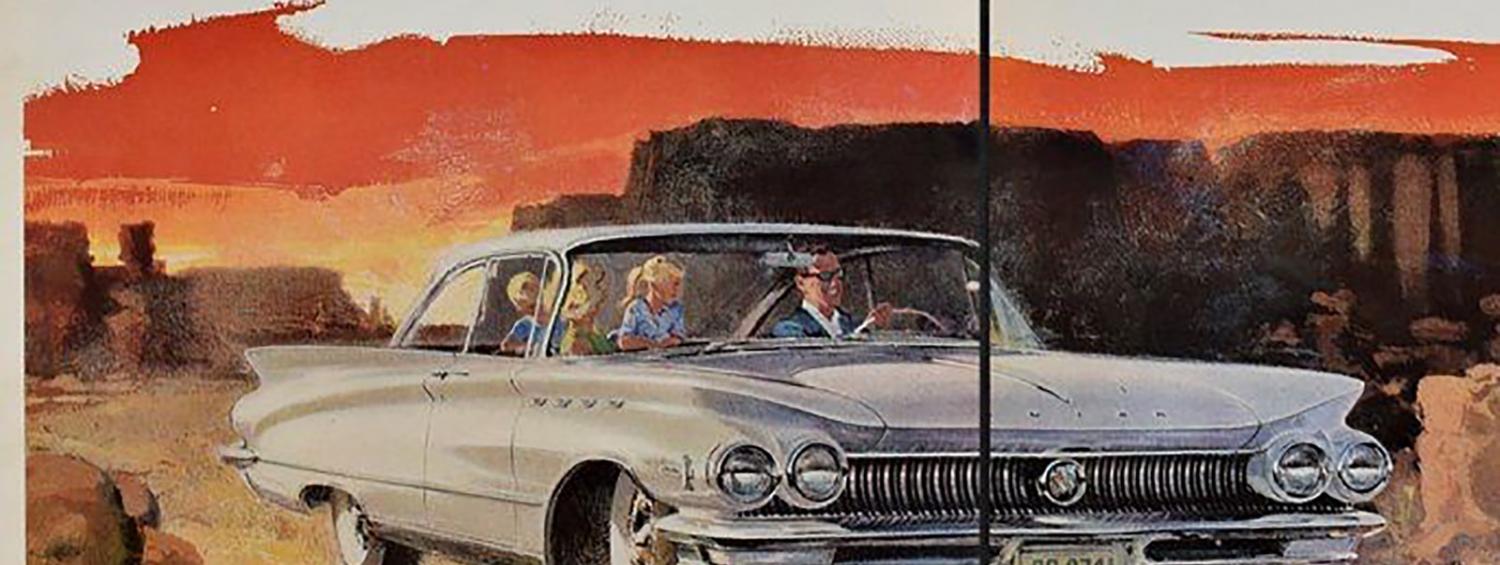

Still, the number of travelers began to grow year by year. As a result, the interstate highway system began to emerge in the 1920s and was further spurred by Depression-era job-creation programs. After World War II, an economic boom meant that most Americans could afford cars. Businesses quickly sprang up to fulfill the needs of travelers, especially motels to offer a convenient place for travelers to stay on the road. In the 1930s, it would take a motorist about three weeks to drive a car across the country. By 1960, it only took four days. The road trip as a type of family vacation quickly became an American tradition. National parks and historical monuments became popular destinations, as well as traveling to attend weddings, funerals, and family reunions.

The Road Trip Story

Road trip stories reach back even before the invention of the car. George Washington wrote and published a road trip story in 1752 about his almost 1,000 miles round-trip journey to deliver a letter to the French before the French and Indian War. Washington became one of the few British citizens to go west of the Appalachian Mountains and the story of a young man traveling on adventurous journey shares many of the same tropes and traditions popular in classic road trip stories. From the introspection of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road to the comedy of National Lampoon’s Vacation, the genre is wide but shallow. Road trip narratives typically feature a story of discovery, spontaneity, and the American landscape, but almost exclusively from the point of view of a white man. Miss You Like Hell interacts with many of the traditional road trip tropes but with a new, more diverse perspective.

The most popular interpretations of the road trip narrative feature a white man (or men) traveling across the country in search of himself or some idealized version of a more peaceful and true sense of the country. Most typically, the protagonist leaves behind the city and heads out with little to no plan. He travels where the road takes him and relies on the kindness of strangers or his own ingenuity to overcome obstacles. Some of the most influential road trip stories to exist in this genre including Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, John Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley in Search of America, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Cruise of the Rolling Junk, and Robert M. Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. Steinbeck summarizes this spirit of spontaneity in his book:

“Once a journey is designed, equipped, and put in process, a new factor enters and takes over. A trip, a safari, an exploration, is an entity, different from all other journeys. It has personality, temperament, individuality, uniqueness. A journey is a person in itself; no two are alike. And all plans, safeguards, policing, and coercion are fruitless. We find after years of struggle that we do not take a trip; a trip takes us. Tour masters, schedules, reservations, brass-bound and inevitable, dash themselves to wreckage on the personality of the trip… The certain way to be wrong is to think you control it.”

In many road trip stories, there is a desire to “go west.” Many journeys terminate generally in the West or specifically in California. In this way, the road trip story reflects the story of American expansion. The Oregon Trail and the Gold Rush are stories of families setting off west with their belongings in search of prosperity and a better life. In road trip stories, travelers head west looking for a more “authentic” American experience. Steinbeck writes, “For many years I have traveled in many parts of the world. In America, I live in New York, or dip into Chicago or San Francisco. But New York is no more America than Paris is France or London is England. Thus I discovered that I did not know my own country.” When not traveling west, travelers are still usually in search of authentic connection, be it with the country, nature, themselves, or their family.

Road trip narratives rely on the kindness of strangers to overcome obstacles. They are frequently a reminder of the humanity and comradery of people on the road. Paul Theroux, writing an account of his cross-country road trip for Smithsonian Magazine wrote “In the 3,380 miles I'd driven, in all that wander, there wasn't a moment when I felt I didn't belong; not a day when I didn't rejoice in the knowledge that I was part of this beauty; not a moment of alienation or danger, no roadblocks, no sign of officialdom, never a second of feeling I was somewhere distant—but always the reassurance that I was home, where I belonged, in the most beautiful country I'd ever seen.” But this idealized version of the road trip has so frequently been a false narrative for women, people of color, and the LGBTQ+ community. Few stories exist that champion the road trip for anyone who is not white and male. Historically, the road is a dangerous place for these groups and the narratives about their journeys are centered on fear and tragedy.

The story of women on the road is almost always one of fear or invisibility. They tend to be escaping from something or are stripped of agency. The female road trip narratives that have entered the national mindset are few and far between. Thelma and Louise is the clear standout, but this film shows the stark difference between female and male road trip narratives. Traditional narratives celebrate the spontaneity and free-spirited joie de vivre of a road trip. Thelma and Louise, while certainly interacting with that idea at some points, prove that for women, those discoveries come at a high price. Road trips taken by women are most often in flight from dangerous situations, and seldom, if ever, for pure adventure.

Vanessa Veselka, a writer and former hitchhiker, wrote a compelling essay in American Reader talking about her experience as a solo female on the road and the feeling that she was set apart from her male counterparts.

“I engendered a fear that seemed to arise from the gap between men and women regarding the social costs of hitchhiking. The pay-to-play price for a woman is just so much higher than for a man. We recognize that, in our world, a woman on the road is marked. She has been cut from the social fabric, excised at such an elemental level that when she steps onto the road, she steps into an abyss. And whatever leads up to that choice inspires in us a primal fear. A man on the road is solitary. A woman on the road is alone.”

What’s taken from women in the road narrative is a sense of agency. In its place is a large roadblock of fear and danger. Still, solo female travelers are on the rise in the United States. 72% of women will vacation solo this year. According to Marybeth Bond, the average adventure traveler is not a 28-year-old male, but a 47-year-old female. Even though female road trip stories are few and far between, female travelers are not. Literary narratives don’t support the idea of a female road trip and according to Veselka, “the only thing more dangerous than having simplistic narratives is having no narrative at all, which is deadly.”

The Green Book helped People of Color navigate around dangerous or unwelcoming places on the road, but these road trips could not have the spontaneous spirit of “seeing where the road takes you.” Allen Pietrobon, a history professor at Trinity Washington University, said in an interview with Citylab that for People of Color before the Civil Rights Movement, “travel is not the fun, lovely, free-flowing, discover-yourself journey. Even the simple things—getting to stop at a gas station or eat at a restaurant—are much more difficult.” As some of the most affordable and most popular road trip destinations, national parks are a cornerstone of the American road trip, but for people of color, they were not always welcoming places. When People of Color traveled to national parks, they were often forced to use segregate campgrounds. Even today, 78 percent of national park visitors are white and 80 percent of National Park Service employees are white.

When the road trip first began, only the wealthiest and most resourceful travelers could afford to take the journey. As travel became easier, no road trip narratives remained chained to a limited perspective. What’s unique about Miss You Like Hell in the road trip canon is its inclusion of a more diverse set of Americans on a cross-country road trip while retaining the spirit of belonging and the kindness of strangers. It is a classic road trip narrative exploring similar tropes—ending in California, visiting Yellowstone National Park, breaking down on the side of the road—but with a new set of characters.

Box Office: 301.924.3400

Open Wednesday - Sunday: 12:00 PM - 6:00 PM